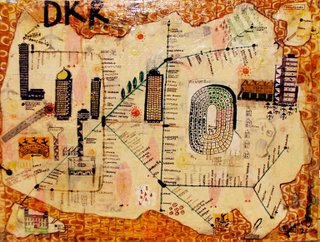

'Young Ireland' vs Old Ireland by Caoimhghin Ó Croidheáin (see http://gaelart.net/)

He who fancies some intrinsic objection to our nationality to lie in the co-existence of two languages, three or four great sects, and a dozen different races in Ireland, will learn that in Hungary, Switzerland, Belgium, and America, different languages, creeds, and races flourish kindly side by side…

Thomas Davis.

Is bréag mór é gur choir go mbeadh náisiúnachas in aghaidh an ilchultúrachais. Síolraíonn an claontuairim sin don chuid is mó ó stair nua aimseartha na hEorpha agus an legáid de Nazional Sozialismus sa Gearmáin agus Nationalismo san Iodáil agus, an cineál ‘Fascismo’ a bhí i réim in Éireann gach re seal suas go dtí na seascaidí. Sa chathair ilchultúrtha, ilteangach darb ainm Baile Áth Cliath, feictear fear ag amharc aníos ó Fhaiche Choláiste i lár na cathrach, a bhí duine de na saoithe ba nua-aimseartha agus ba intleacthúla in Éireann dá linne, agus ba ainm do Thomas Davis. Protastúnach, réabhlóideach, file, uomo universale ba ea é agus de bhunaigh sé an páipéar ‘ The Nation’ i 1840. Ag an am, bhí an páipéar sin fíor-choitianta ar fud fad na tíre agus do thug sé léagas intleachúil agus cultúrtha chomh maith le dóchas polaitúil agus sóisialach do mhuintir na tíre. Bhí dearcadh leathan Eorpach ag Davis agus a chomhráidithe agus bhí sé mar intinn aige fuinneamh na tíre a mhúscailt agus cultúr nua-aimseartha a chruthú ó scartha den oidhreacht náisiúnta agus Éireann a chur ar ais i gcróilár de chultúir na hEorpa.

Ach i ré an Davis agus a leithéid bhí ciall agus fealsúnacht ag baint le gluaiseachtaí phobail, gluaiseachtaí chultúrtha. Sa lá atá inniu ann tá níos mó ‘spectacle’ ná ciall, níos mó ghlóir ná ceol. O thosaigh ‘Macnas’ ag sionsáil ar son na hÉireann breis is deich mblian o shin, is féidir linn iad a chloisteáil go minic ach níl morán le cloisteáil, faraor! Céard a cheapfadh Davis de sin? An mbeadh sé dearfach faoi threo cultúrtha na hÉireann?

Níl mé a rá nach bhfuil aon mhaitheas le sionsáil. Is cuimhin liom nuair a bhí mé ag teacht ar ais go hÉireann san Aerfort Charles de Gaulle I bPáras. Bhí oibrithe ag dul thart le drummaí agus bhí an glóir dofhulaingeach. Ba inimircigh formhór acu agus diúltaigh siad na leithris a ghlanadh. Sa chas sin, chur siad in iúl dúinn go han éifeachtach go raibheamar go léir ag brath orthu agus, ní raibheamar in ann a shéanadh go bhfuil an streachailt aicme fós beo. Bhí ciall agus cuspóir an-éifeachtúil ag baint leis seachas sionsáil páisteach dochríochnaithe.

bréag mór- big lie

ilchultúrachas- multiculturalism

claontuairim- prejudice

ilteangach-multilingual

nua-aimseartha-modern

fíor-choitianta- extremely popular

dearcadh- perspective

dearfach-positive

sionsáil.-drumming

inimircigh- immigrants